As students of the Urantia papers, should we take seriously “the Isle of Paradise?” What about “space potency” and “force organizers?” If we can accept such things, then it seems reasonable to take one more step, and take seriously their description of the ultimaton, “the first measureable form of energy.” [Paper 42:1.2]

As students of the Urantia papers, should we take seriously “the Isle of Paradise?” What about “space potency” and “force organizers?” If we can accept such things, then it seems reasonable to take one more step, and take seriously their description of the ultimaton, “the first measureable form of energy.” [Paper 42:1.2]

Given all this, we find ourselves face to face with a fascinating challenge: how to connect ultimatons to the actual physics and technologies that allow mobile phones and GPS satellites to work. As we know, the chips inside our phones exploit some kind of “quantized mechanics,” while the satellite navigation system requires the sort of relativity “faintly glimpsed” [Paper 195:7.5] by Einstein.

Sadly, our current best ideas for explaining how all this works—our “standard models” for quantum field theory and relativity—are incompatible with each other. But what if The Urantia Book could show these two theories how to “play together?” This is the question I explore in the first half of an upcoming video. In the second half, I consider some of the implications of what The Urantia Book reveals, first with regard to black holes, and then with regard to the Milky Way. The next few pages give a brief preview.

Since the Milky Way is more fun to discuss than collapsed matter, let’s begin with a glimpse of the new perspective The Urantia Book offers on the Milky Way. Of course the first question must be: how well do Urantia Book descriptions match up with the data our astronomers can measure?

With regard to distances, we are warned that our use of redshift to estimate distances in outer space will lead to wildly erroneous estimates. [See paper 12:4.14]

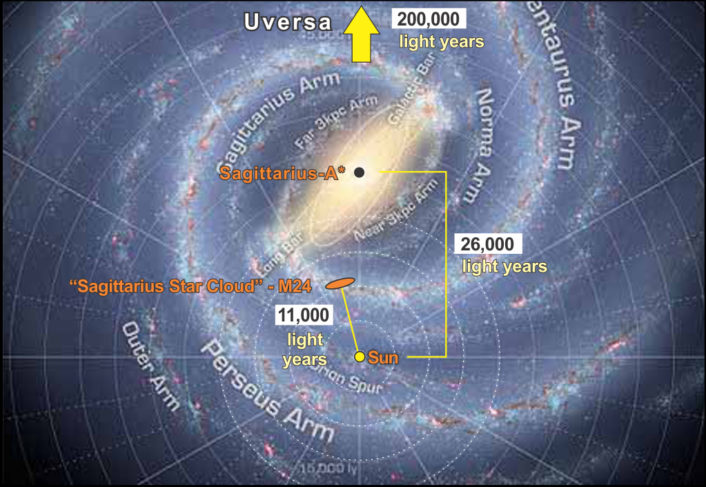

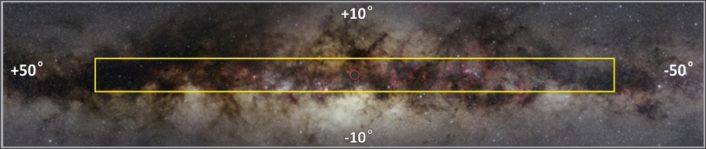

On the other hand, they confirm that our toolbox of astrometric techniques should allow us to measure local distances “most precisely.” [Paper 41:3.10] Encouraged by this comment, in this first picture I show some of the local features we’ve been able to measure, together with that surprising distance of “200,000 light years” to Uversa. [Paper 32:2.11]

With this “map” (extrapolated view from above) in mind, let’s take a fresh look at this description:

The rotational center of your minor sector is situated far away in the enormous and dense star cloud of Sagittarius, around which your local universe and its associated creations all move, and from opposite sides of the vast Sagittarius subgalactic system you may observe two great streams of star clouds emerging in stupendous stellar coils. [Paper 15:3.5, page 168.1]

Notice that “dense star cloud of Sagittarius” is distinct from “vast Sagittarius subgalactic system.” The first half of this paragraph refers to the rotational center of our minor sector, Ensa. This “enormous and dense star cloud of Sagittarius” is M24, about 11,000 light years away. But the rest of the paragraph appears to refer to the rotational center of our major sector, Splandon. Those “two great streams of star clouds” can be seen “emerging in stupendous stellar coils” from opposite sides of Sagittarius A* (SgrA*) which astronomers have been able to measure (“most precisely”) as being 26,000 light years away. Notice also that Ensa is associated with a single dense star cloud, while “the vast Sagittarius subgalactic system” is associated with a stream of such star clouds.

In this light, that “200,000 light year” distance to Uversa becomes interesting. If we allow that SgrA* marks the center of Splandon, then the revelators have revealed that Uversa lies 174,000 light years behind Umajor the Fifth.

Next, let’s consider this:

If you could look upon the superuniverse of Orvonton from a position far-distant in space, you would immediately recognize the ten major sectors of the seventh galaxy. [Paper 15:3.4, page 167.20]

The vast star clouds of Orvonton [major sectors?] should be regarded as individual aggregations of matter comparable to the separate nebulae observable in the space regions external to the Milky Way galaxy. [Paper 15:4.9, page 170.3]

What might this distribution look like from above? If we were Force Organizers looking down onto Orvonton (from above), what would we see? Since each major sector has its own center of rotation [Paper 15:3.12], and all ten are in orbit about Uversa [Paper 15:3.13, I imagine we’d see something like ten electromagnetically bright spirals of gravita, embedded in ten whirlpools of electromagnetically dark ultimata:

The Sagittarius sector and all other sectors and divisions of Orvonton are in rotation around Uversa, and some of the confusion of Urantian star observers arises out of the illusions and relative distortions produced by the following multiple revolutionary movements… [Paper 15:3.7, page 168.3]

5. The rotation of the one hundred minor sectors, including Sagittarius, about their major sector. [Paper 15:3.12, page 168.8]

6. The whirl of the ten major sectors, the so-called star drifts, about the Uversa headquarters of Orvonton. [Paper 15:3.13, page 168.9]

I expect that we’d also find all ten major sectors are “co-planar,” i.e. they share a common plane. Let’s speculate about the distribution of these major sectors within such a “superuniverse plane.”

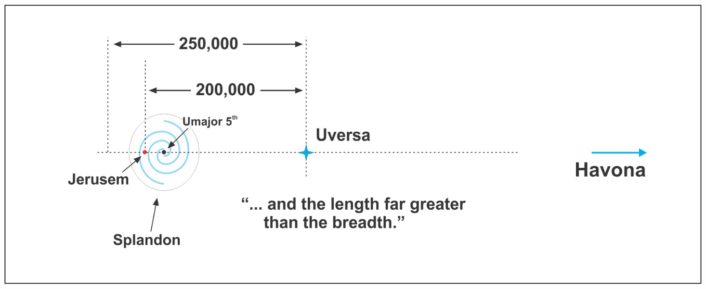

Recall that these ten sectors are arranged so that the “length” of Orvonton is “far greater than the breadth” [Paper 15:3.2]. Think what this implies: since it’s 250,000 light years from the outskirts (near Nebadon) to Uversa, and since Uversa is centrally located, should we assume that Orvonton extends (more or less) a similar distance on the opposite side? If so, then this implies a “length” for Orvonton on the order of 400,000 to 500,000 light years.

But they reveal that this length is far greater than Orvonton’s breadth. From what we can see given our location in space, native astronomers estimate the breadth of this system to be about 100,000 light years. Despite our view of things being greatly obscured, we can nevertheless conclude that Orvonton must have a distinctly elongated shape, extruded by the tidal effects of Paradise gravity (acting for over a trillion years) towards the center of all things.

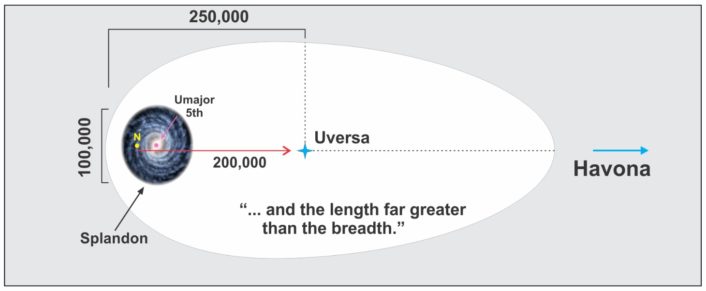

But here’s the surprise: they also state that the breadth of this distribution is “far greater than the thickness.” Our astronomers estimate that about 80% of the stars in our sector of Orvonton lie within a disk less than 1,000 light years thick. Not surprisingly, astronomers call this core distribution the thin disk. The so-called thick disk is less than 5,000 light years thick.

Here its worth “pausing to consider” these three numbers: length 500,000 light years, breadth 100,000 light years, thickness 5,000 light years. The authors appear to be describing Orvonton as a vastly elongated, extraordinarily flat, pancake. How thin is this pancake? With a length to thickness ratio of 100:1, this pancake has the same relative thickness as a DVD—10 cm wide by 1 mm thick.

To help make sense of these numbers, here’s that “200,000 light years” in context:

If we put all this together with their statement, “Nebadon is now well out towards the edge of Orvonton” [Paper 32:2.11], then we get something like this:

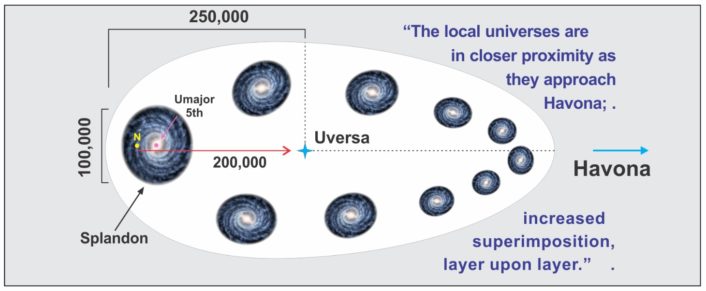

But in Paper 15, section 3, they also explain that the local universes of Orvonton are clustered (packed together more closely) on the far side of Orvonton:

The local universes are in closer proximity as they approach Havona; the circuits are greater in number, and there is increased superimposition, layer upon layer. But farther out from the eternal center there are fewer and fewer systems, layers, circuits, and universes. [Paper 15:3.16, page 168.12]

Given what the authors chose to reveal, it looks like the so-called “sun-forming nebula” centered on and rotating about Sagittarius A* (SgrA*), must be much more than a local universe, but somewhat less than a superuniverse. Which implies that this vast spiral may actually form the bulk of a single major sector (Splandon), and that the other nine major sectors tend to contract and cluster on the Havona side.

What could cause such clustering? Recall that (in this Urantia Book scheme) this superuniverse system of swirling major sectors (a) floats in a rotating pool of ultimata, which is (b) orbiting Paradise in a beltway of segregata, which is (c) flowing along its “curved space path of lessened resistance to motion,” and (d) that not far off to the right (in the pictures above) sits the source and center of gravitational control for the entire master universe. And (e) that Paradise grips matter by its ultimatons.

Of course, in a young, “Big-Banged” universe, this sort of distribution is not what astronomers would expect. Such a scheme implies what one student has called “a new cosmological theory.” My approach is that The Urantia Book is presenting a new cosmological theory, and I’m simply exploring the scientific implications.

Nevertheless, as a student of astronomy, I almost feel like apologizing for proposing such an astronomically outlandish model. But let me explain. This adventure began when I noticed the revelators had posed an interesting question: “What’s the relationship between gravita, and the pool of ultimata within which that gravita forms?” Let’s explore this line of thought.

In The Urantia Book story, before you can have hydrogen, and thus suns, you need a reservoir of ultimatons. It’s these ultimatons that “power directors” can arrange into the type of matter that interacts with light. So before we can have this “type of matter that interacts with light,” we need those ultimatons. For students of The Urantia Book, this seems like a reasonable starting point.

In the four parts of the upcoming video (1. Foundations, 2. Mass & Matter, 3. Dark Islands, 4. Milky Way) I try to map out what The Urantia Book reveals about the ancestry and interactions of ultimata or “emergent energies” [Paper 42:2.10], and how these ultimatonic underpinnings might determine the gravitational dynamics acting within and upon Orvonton, and what our astronomers might expect to measure. The crucial bits being (1) ultimatons have mass; (2) being pre-electronic, ultimatons do not interact with electromagnetic light; and (3) being intimately connected with the cause of weak hypercharge (“zilch”), clusters of ultimatons interact aggressively with this now famous Higgs-type field (“primordial force-charge”). Anyone keeping up with either particle physics or astronomy will be struck by how neatly ultimata solves the two outstanding issues of our standard models: (1) invisible mass, and (2) the energy of quantized fields.

With regard to the origin of ultimatons, “pause to consider” the way an Associate Master Force Organizer injects angular momentum into the foundations of finite physics: in some region of space potency, the (eventuated) presence of a Primary (Paradise) Force Organizer segregates an island of “pure energy” (see segregata, Paper 42:2.9.) When an associate force organizer shows up, his transcendental presence imposes some kind of chiral torque on this island, which starts to rotate.

Picture the situation: we have an island of segregata within which a halo of “emergent energies” (see ultimata, Paper 42:2.13) condenses. This massive halo of ultimata is locked onto, and rotating about, an irresistible center of rotation. In this picture, there’s not yet any source of friction, so we have an increasing quantity of angular momentum being generated within a superfluid medium. As our own physics has discovered, angular momentum in a superfluid naturally disperses, but it cannot disappear. So the angular momentum injected by that associate force organizer into his halo of ultimata dissipates into smaller and smaller vortices, until some minimum “quantum of vorticity” (spin), is achieved.

As a thought experiment, let’s use that minimal vortex to help define an ultimaton. Recall that a “mature ultimaton” has a well-defined response to absolute (Paradise) gravity. However,

Ultimatons are capable of accelerating revolutionary velocity to the point of partial antigravity behavior [Paper 42:6.3, page 476.5]

If we define the “mass” of an ultimaton as its response to Paradise gravity, then paper 42:6.3 implies that ultimatons achieve a maximum of such “mass” when they have that minimum quantum of spin. As an ultimaton’s “velocity of axial revolution” [Paper 42:6.6] increases, its response to Paradise decreases.

What I’d like to propose is that this coupling of (minimum spin) + (maximum mass) defines what we might call “the ground state of the mature ultimaton.” And that each galactic collection of superuniverse major sectors floats in a rotating pool of such ground state ultimatons.

To help break the ice with this “new cosmological theory,” here’s a simple and game-changing point: as students of these papers, what we’re considering is not how (linear) gravity may have nudged galaxies around for a mere 13 billion years. What we’re exploring is The Urantia Book story of how 70 major sectors were “force-organized” (in place) within a sheet of segregata centered on nether Paradise. And that this happened hundreds of billions of years before any spirals began to form in the outer space levels. And that an ancient, central and relatively small “grand universe” needs to be distinguished from the far younger systems we can see evolving in the outer space levels of a vastly larger “master universe.”

These are the sort of things I explore (in a Urantia Book-reader-friendly way!) in that video, being recorded in four parts (4A: Foundations, 4B: Mass & Matter, 4C: Dark Islands, 4D: Milky Way).

Parts 4A and 4B are ready, and can be found here: Click here

If anyone would like to help adjust the content and presentation in these videos, please let me know!

P.S. “Galaxy” and “Milky Way”:

Regarding The Urantia Book’s use of the terms galaxy and Milky Way, the ancient term Milky Way (“via lactea”) was coined not to label a nebula or galaxy, but to describe what our ancestors saw when they looked up—a milky splash across the sky. As an observant reader pointed out, most of the instances of “galaxy” in The Urantia Book are used to mean “many” or “collection.” Which is consistent with the idea of Milky Way as a galaxy (collection) of ten vast sun-forming spirals, each similar in appearance to M31.

When considering the use of these terms in The Urantia Book, another thing to keep in mind is this: in 1934, what did astronomers see when they looked in the direction of Uversa? Up until the 1960’s, the best view we had of the so-called “Milky Way” looked something like this:

Non-astronomers may not realize that almost all the stars visible to optical telescopes along the dense diameter of this milky splash (“via lactea”) are “far, far” less than 20,000 light years away. So if we are to take seriously their revelation that Uversa lies 200,000 light years away in the direction of the center of this dense diameter, then Uversa lies “far, far” beyond this foreground wall of gas, dust clouds and stars.

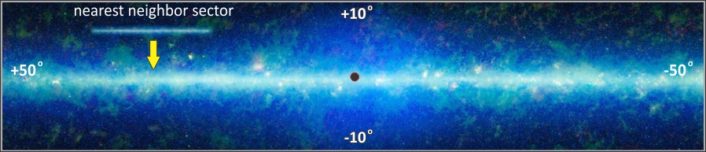

Even with “improved telescopic technique” [Paper 41:3.10], below is what the Spitzer Space Telescope revealed, using light in the near infrared (1-5 microns):

The issue this data implies is that if all ten major sectors lie in a common plane less than 5,000 light years thick, with 80% of the stars in each sector locked into disks a mere 1,000 light years thick, then even with our current best telescopic techniques, our neighbor major sectors, and Uversa itself, remain almost completely hidden behind this infrared “line of avoidance.” The video at the following link illustrates the problem, comparing our best infrared and visible views using the “GigaPixel” data released in 2012:

http://www.eso.org/public/videos/eso1242a/ [see the 70MB, HD 720p version]

As we can see, there really is a wall blocking our view towards Uversa!

Of course this does not change the hard fact that:

… when the angle of observation is propitious, gazing through the main body of this realm of maximum density, you are looking toward the residential universe and the center of all things. [Paper 15:3.3, page 167.19]

Given all the above, while it is quite correct for the revelators to say that Uversa is located “far, far away in the dense diameter of the Milky Way”, it may be even more correct to say that “when the angle of observation is propitious”, Uversa lies 174,000 light years directly behind Umajor the Fifth, the center of rotation we call Sagittarius A* (SgrA*), the physical center of our major sector, Splandon.

But what makes all this even more interesting is the way a cluster of such superuniverses fits neatly at the center of Marshall L. McCall’s famous “Council of Giants” (see https://arxiv.org/abs/1403.3667), that nearby ring of 12 giant galaxies surrounding our relatively tiny—but absolutely extraordinary—place in space.